Last year, I submitted an Emmy Noether proposal to the DFG, Germany's flagship program for early-career researchers to establish independent research groups. The proposal outlined a vision for building robust, modular AI systems: frameworks for orchestrating multi-component workflows, hierarchical state management, runtime specialization, and transactional semantics for fault tolerance.

I recently learned it was rejected.

And yet, here I am, feeling oddly celebratory.

As a side note before I continue: writing publicly about a rejected grant is unusual. Most academics, myself included until now, quietly move on when these things happen. We do not talk about rejections; we hide them. But I think there is value in shining a light on the process, both for my own reflection and for others who find themselves in similar positions, whether it is a rejected grant, a declined paper, or any setback in a career built on external validation. If this helps even one person feel less alone in that experience, it will have been worth the vulnerability.

The Curious Case of Being Too Early

The reviewers' concerns were reasonable on their face: the scope was ambitious, the preliminary work was nascent, the risk was high. One reviewer worried the project would be "overtaken by developments" in the rapidly moving field. Another noted that existing frameworks might already address the core challenges.

These critiques reveal something interesting about how we fund research in Germany (and elsewhere). There is a tension between wanting transformative work and preferring proposals where the path is clear and the risk is manageable. The academic community often speaks of valuing moonshots while quietly rewarding incremental advances with well-trodden methodologies.

I do not say this bitterly. To be honest, had I been sitting on the other side of the table, I might have rejected it too. It was not the best proposal ever written, and I am not claiming it was. When you are allocating limited resources, betting on the safer horse makes sense. But it does mean that proposals aimed at defining the next frontier, rather than refining the current one, face an uphill battle.

The Vindication

Here is the thing: everything in that proposal has been validated by the field's trajectory.

"This project aims to develop a comprehensive, modular framework designed specifically for dynamically assembling and orchestrating multi-component AI workflows. Existing solutions often lack robust mechanisms to integrate diverse AI components seamlessly, dynamically specialize models for different tasks, and reliably maintain system state and execution consistency."

— Laurent Bindschaedler, Emmy Noether Proposal, March 2025

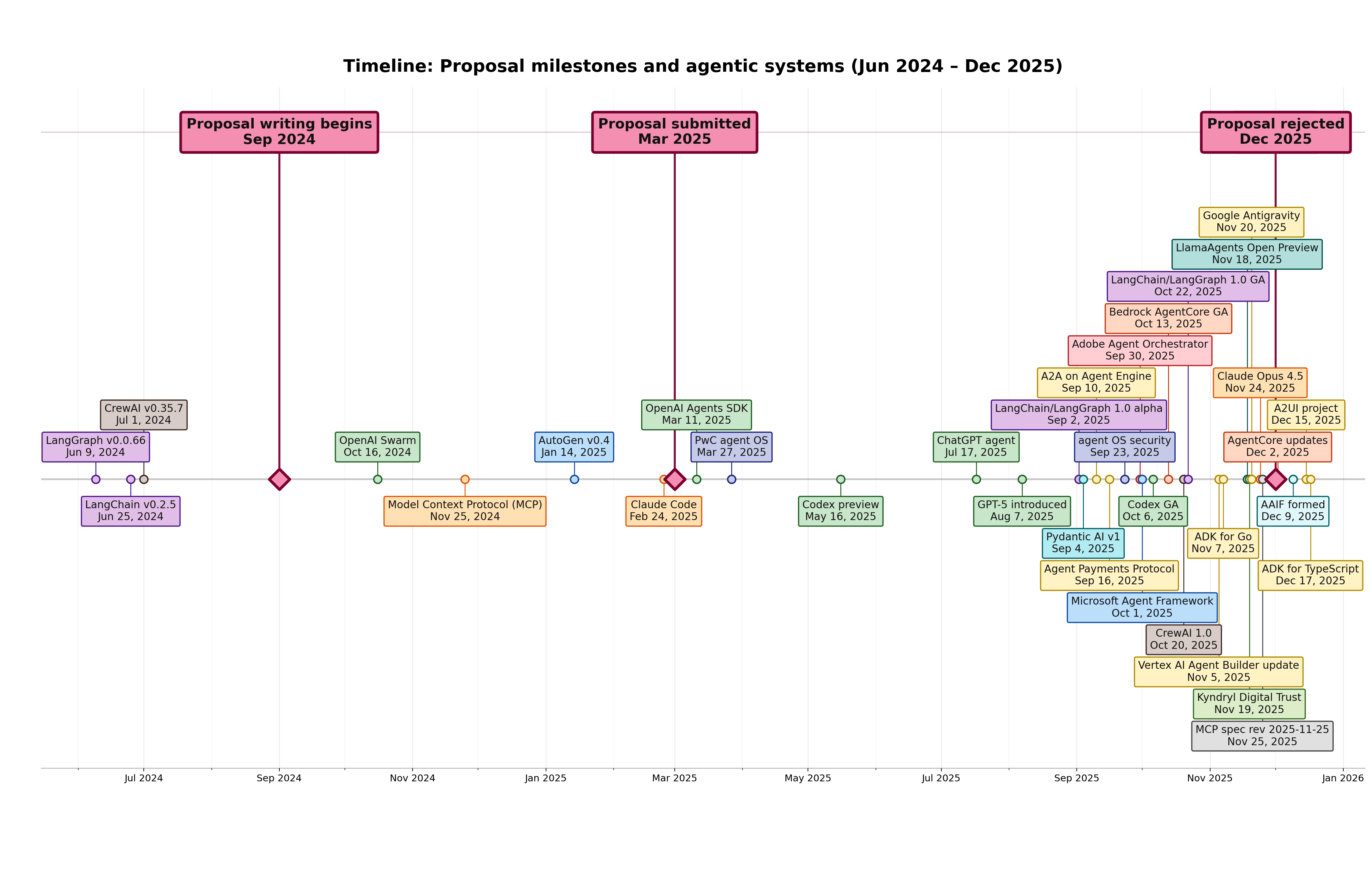

When I wrote about the need for orchestration frameworks to compose AI components dynamically, the landscape was sparse. Now we have a Cambrian explosion of agent frameworks — LangGraph, CrewAI, AutoGen, Claude Agent SDK — all wrestling with exactly the problems I identified. When I argued that state management and context engineering were fundamental challenges, the discourse was dominated by model scaling. Now context engineering and multi-agent orchestration are on everyone's lips.

The Coding Tools Revolution

Perhaps most strikingly: in 2024, I was describing systems that would dynamically orchestrate AI components for complex software engineering tasks, among others. In 2025, Claude Code and OpenAI Codex launched and fundamentally transformed how software gets built. Claude Code alone reached $1 billion in annualized revenue in less than a year. Claude Code recently introduced skills, and OpenAI is doing the same — essentially implementing the dynamic specialization a couple of my summer interns worked on two years ago. The proposal was submitted in March 2025; by the time the rejection arrived, much of what I had proposed was already shipping in production.

The Work Continues

This is the part that matters most: the work does not stop because a funding body said no.

The vision I articulated remains my north star. Modular AI systems. Robust orchestration. Stateful architectures. Failure-tolerant workflows. These are not just interesting research problems; they are the problems that will determine whether AI systems can be trusted in consequential settings.

My group continues to work and publish in these directions. We are building the infrastructure. We are running the experiments. We are contributing to a future where AI systems are not just impressive but reliable.

And while these existing systems have achieved much of what we envisioned, they have not gotten everything right. There remain open problems in state management, fault tolerance, and dynamic composition that the current generation of tools handles imperfectly at best. We are building our interpretation of what robust AI infrastructure should look like and will open source it later this year.

Funding is helpful. Funding is not permission.

Academia in Fast-Moving Fields

I want to be careful here, because I have deep respect for the German research ecosystem. The DFG, the Max Planck Society, and the broader academic infrastructure have provided me with extraordinary opportunities.

But I do think there is a broader conversation to be had about how we evaluate ambitious proposals. When a rapidly evolving field is at stake, caution can become conservatism. The worry that "industry will get there first" is sometimes used to justify not funding academic work, but that reasoning, taken to its conclusion, would have us cede every fast-moving area to the private sector. Perhaps the real question is: what is academic research for, if not to take the risks that industry cannot or will not?

There is a deeper structural issue worth naming: this entire space is moving at a pace that traditional academic processes were never designed for. Decades of research are being compressed into years. Industry is, in many ways, ahead of academia — not because academics lack vision, but because companies have vastly more resources and the machinery of grants, publications, and peer review operates on timelines that no longer match reality. We are often looking at the same problems, just with different perspectives, different objectives, and different timeframes.

The irony is stark: maybe 50% of the five-year research agenda I proposed has already been addressed by industry in the time since I submitted. Yet, two of the reviewers felt my proposal was too ambitious. The field moved faster than any of us expected.

A note of self-criticism: some will say we should have moved faster, published more, and released sooner — and I suspect senior faculty in my own institute would say the same about my group. They would not be entirely wrong. But a small research group with a few students, however motivated, cannot truly compete with corporations deploying hundreds or thousands of engineers and billions of dollars. We do what we can with what we have, and we have to pick our battles while moving as fast as we can.

This mismatch affects everything:

- Grant processes that take 8-12 months from submission to funding decision

- Publication timelines where a paper accepted today describes work from a year ago

- Peer review cycles that assume reviewers have time to deeply engage with rapidly evolving subfields

I do not have a solution to offer here. But I do think we need to acknowledge the problem. If academia wants to remain relevant in fast-moving fields, we need to rethink our timelines, or accept that our role is increasingly to provide foundations and frameworks while industry builds the applications. But in this field, industry already owns the infrastructure, the rails, and most of the frameworks.

Acknowledgments

Despite the outcome, I want to express genuine gratitude. To the reviewers: thank you for your time and thoughtful feedback, even in rejection. To the DFG and MPI: thank you for the opportunities and infrastructure that make this research possible in the first place. To my students: thank you for your hard work and for believing in the vision even when the path is uncertain. And to my collaborators: thank you for your continued support and for pushing the work forward alongside me.

Looking Forward

I will resubmit. The proposal will be sharper, the preliminary work stronger, the vision refined by another year of evidence. Maybe I will be wrong about some things; the field is moving fast enough that everyone will be somewhat wrong. And if it is rejected again, I will keep going anyway.

Some ideas are too important to abandon because of a funding decision. Some bets are worth making even when the odds are uncertain.

If you asked me today whether, given the chance, I would be researching anything else, even if it meant more publications or faster recognition, my answer would be a resounding no. From where I stand, building reliable AI systems is the most important problem in computer science right now. Nothing else even comes close.

The future of AI must intersect with systems. I believed it five years ago (it is why I chose MIT for my postdoc). I believe it now. And I intend to help build it, one way or another.